Flint Knapping: Everybody’s Universal Heritage

We’ve gone on and on in the knives section about knapped blades. Here’s how we make them. Put simply, knapping is the art of making tools from stone. Regardless of who we are and where we came from, we all have this common thread in our collective ancestry: all of our ancestors made and used stone tools at one time or another in history. There are a few cultures today who still make and use stone tools, and the largest group is probably right here in the United States. Knapping is a very fast growing hobby, with between 5,000 and 10,000 knappers in the USA alone.

Only a few types of stone are “knappable.” Flint, chert, agate and obsidian are the most common, but man-made glass and porcelain are also knappable. The common thread throughout these rock species is the ability to fracture “conchoidally.” Conchoidal fracture is a big term for the characteristic breakage a BB makes when your kid shoots the front window. We all recognize this, a tiny entry hole, and a large exit. Our ancestors discovered this action in certain rock types, and were able to expand this one characteristic into mankind’s first technology.

Forgotten a scant few years after the entry of metals into each stone age culture, hobbyists and archeologists are working hard to rediscover the lost secrets of the earliest of technologies.

This is a quick and dirty exposition of the basics of how we make our stone blades. The following pages are very graphic intensive, so those of you who have slow, soda straw connections to the World Wide Web, please bear with us.

Thanks, we hope you enjoy it.

Tom Sterling and Joe Higgins

Ancient Art, Modern Fun

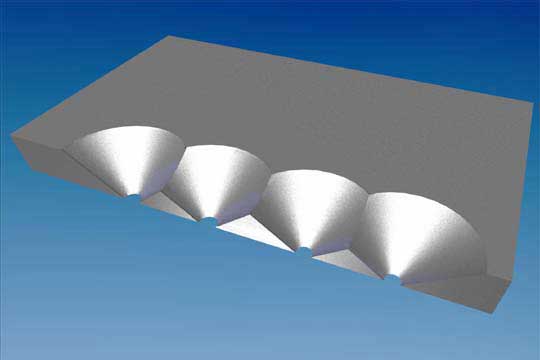

Conchoidal fracture is the secret to knapping – the characteristic breakage of glass from a BB hit. Seen here, the conical spall broken from a piece of glass, with the edges of the cone 110 degrees from the path of the BB.

Here the BB has hit along the edge of a piece of glass. Still the same characteristic spall taken from the glass, just in half.

Here a series of BB hits carefully spaced along the edge of the glass, overlapping neighboring spalls. This is the basic method of selectively removing material to end up with the desired shape. Each action from here on is identical, simply removing a piece of the conical spall where desired. Of course, this is the theory. The actual practice takes a little more finesse.

Modern Knapping Tools

These are typical tools used in what we’ll call “Modern Knapping.” The business ends are made of copper, which turns out to be an excellent simulation of the antler and soft hammer stones used by the ancients. Modern knappers tend to favor these because they are inexpensive and easily obtainable, and reduce pressure on deer and moose populations. There are examples in the archeological record of prehistoric use of copper tools made from naturally occuring pure copper.

Here’s a dissenting comment posted by Dan Stueber (http://www.thunderstones.com). I’ve posted it verbatim as he sent it. Thanks for your input, Dan: You’ve written a very nice article, but I would like to point out one misconception.There is absolutely no archaeological evidence or archaeological reports written about the use of copper billets prehistorically, none! There’s a paper by Whittaker and Stafford reporting on extensive research in the Great Lakes copper region of North Americ. They report on evidence for copper pressure flaker tips, but no billets were found. Copper lasts for a very long time in the soil. I have been doing very detailed technological debitage analysis for over 25 yearson sites I the western states, millions of flakes, looking at every flake under magnification and have never seen copper residue on a flake. I have see copper on a some “fakes” in collectionownedby unsuspecting collectors. Ötzi, the Ice Man of the Tyrol had a copper axe, he also had an antler pressure flaker. Experiments that have been conducted using natural nuggets for billets show that they, in fact, don’t work for billets, the natural copper is too hard. Copper used by modern knappers has been extensively processed when before formed into wire and rods. The pressure flaker tips reportedby Whittaker and Stafford had been very extensively hammered small nuggets formed into short tips that we remounted into handles. If you have any contrary evidence to offer please share it with me.Thanks,Dan Stueber

The tool on the far left is a “copper bopper” for percussion knapping made from a modern copper plumbing cap, filled with lead and wooden shaft. The middle tool is a “copper bopper” made from solid copper rod, used for making large spalls from large rocks. This tool rapidly reduces a rock to smaller, thinner sections or absolute junk, depending on the knapper’s skill level. The tool on the right is a pressure flaker, used for taking small, precise flakes from rock. The business end is made from small diameter copper rod or wire, hammered into a blunt point, and set in a handle of varying materials. This one is made from deer antler, with an adjusable brass collar.

Typical knappers today might have several sizes of each of these for both small and large scale work.

Ancient Knapping Tools

Here are two examples of tools prehistoric people would have used, and which are used today by some knappers (typically called “abo” knapping). The top tool is a pressure flaker, and is the tip of a deer antler (in this case a naturally shed antler). The bottom tool is a percussion billet made from the section of deer antler where it attaches to the skull (also from a naturally shed antler).

Here’s the actual theory put into action. Doc Higgins is holding a piece of “Silver Sheen” obsidian (named because of the gray layers in it) that he’s going to turn into a seven inch blade. This is a large, angular and knobby piece of obsidian, a naturally occuring volcanic glass. Native Americans favored this material for stone tools, using it whenever they could obtain it.

Note the heavy leather glove on his left hand, and the thick leather pad on his leg. The flakes he’ll be removing are said to be the sharpest edge known to man. Because of the conchoidal breakage characteristics of obsidian, the edge produced is feathered out to an edge one molecule thick, far sharper than the best surgical steel.

Here Doc’s about to take the first in a long series of flakes from the obsidian. He’s using a solid copper bopper here, and will be hitting about one third of the way up from the bottom of the edge nearest the bopper. The flake will detach from the uderside of the stone. By controlling where he hits the stone, the angle he holds it, the angle he strikes it at, and the force of the blow he will gradually remove unwanted portions, resulting in a beautifully flaked blade with matching flake scars. He’s been doing this since about 1990, and is self taught. I’ve (Tom) been doing this for about two years, and can produce blades only half the size Doc can, and not nearly as pretty. I also break quite a few. For me, a tragic case of theory wildly outstripping performance. While anyone can learn to knap successfully, truly beautiful work requires lots of practice and extreme dedication.

Here Doc has struck off the first large flake and is holding it in the position it came from. You can see the edges as dark black lines. After studying the rock carefully, he has chosen this particular corner because of the ridge you see running under his thumb. Flakes tend to follow ridges quite well, and a skilled knapper can direct which direction a flake will run.

Here is the same flake removed from the rock. Note that it is a portion of that same spall cone we looked at in the beginning when a BB hits plate glass. Doc will simply remove more portions of similar cones at places (and sizes) of his choosing, until he ends up with the desired results.

Here Doc has removed the second flake, overlapping the first and along the edge ridge he created with the first flake.

Here’s the rock after Doc has carefully removed almost all of the outer layers (the cortex). Note a little of it still remaining at the right hand end. The cortex is highly weathered and doesn’t have that characteristically shiny obsidian surface. The rock is becoming more and more convex in cross section, which is Doc’s ultimate aim. Flakes will travel very well over a convex surface, and convex blades have the best characteristics of both strength and sharp edge for durability.

As the edges become thinner and sharper, Doc is paying particular attention to thickening the incredibly sharp edge by abrading it away with a coarse stone. Modern knappers use pieces of grindstone, where prehistoric knappers would have used coarse sandstone. Thickening the edge allows the force of each blow to transfer efficiently into the stone, resulting in a clean break, in the desired place, rather than allowing the sharp but weaker edge to crush. Crushing either fails to detach a flake, or only allows the break to travel part way into the stone, then break off leaving an ugly ledge which will be very difficult to deal with later (a common beginner’s mistake). A not to be overlooked advantage to abrading the edge is the stone is much safer to handle. Freshly flaked edges are so sharp you can easily cut yourself and not even notice until the area around you begins to fill with red fluid!

Here’s the rock several series of flakes later, at a stage called a “biface.” This is the stage at which Native Americans would have used to transport the stone for trading or taking home. Rather than carrying a lot of waste stone (remember, no pickup trucks back then), Native Americans would have reduced the raw stone to this stage, and carried them away in baskets. From this stage, a large knife blade or spear point could be produced at will, and most of the subsequent waste flakes taken off would be recycled as small cutting tools or arrow points.

Here it is from a side view. At this stage, the rock is at least half the weight of the original.

Here’s the next stage. Doc has continued to go around the edges and on both faces of the stone removing flakes to further refine the shape. He’s been paying especially close attention to removing flakes to help thin the stone.

The same stage edge on. Note how much thinner it is.

Several more rounds of thinning and shaping flakes. Note how much it is starting to look like a knife blade.

More refinement. Doc’s carefully programmed flake removals are starting to show up regularly spaced and matching with flakes from the opposite side. Knappers would refer to these as well spaced flake scars. Nicely patterned flake scars produce prettier blades, and are often considered a demonstration of the knapper’s prowess.

Edge on. Only a few places to fiddle with and we’ll be done.

Here’s the “debitage” (waste stone) pile left after finishing the blade. Many of these flakes are useable as cutting tools simply by abrading the side held next to the hand (for safety), or to be made into smaller knives, arrow points, drills, scrapers or other tools. This is also the amount of material a Native American trader would not have had to carry when he (or she) took out only biface stage material.

The finished 7 inch blade. Note the evenly spaced flake scars, matching with other scars from the opposite side, and smooth edges. A beautifully knapped knife blade, or with several knotches at the wide end, hafted onto a spear. All told, several hours of intense concentration, and lots of years of practice in the school of hard knocks, cuts, scrapes and jabs.

You’ve written a very nice article, but I would like to point out one misconception.

There is absolutely no archaeological evidence or archaeological reports written about the use of copper billets prehistorically, none! There’s a paper by Whittaker and Stafford reporting on extensive research in the Great Lakes copper region of North Americ. They report on evidence for copper pressure flaker tips, but no billets were found. Copper lasts for a very long time in the soil. I have been doing very detailed technological debitage analysis for over 25 yearson sites I the western states, millions of flakes, looking at every flake under magnification and have never seen copper residue on a flake. I have see copper on a some “fakes” in collectionownedby unsuspecting collectors. Ötzi, the Ice Man of the Tyrol had a copper axe, he also had an antler pressure flaker. Experiments that have been conducted using natural nuggets for billets show that they, in fact, don’t work for billets, the natural copper is too hard. Copper used by modern knappers has been extensively processed when before formed into wire and rods. The pressure flaker tips reportedby Whittaker and Stafford had been very extensively hammered small nuggets formed into short tips that we remounted into handles. If you have any contrary evidence to offer please share it with me.

Thanks,

Dan Stueber

Thanks for your interesting input, Dan. I’ve posted your dissension in the body of the article in question.

Tom

One thing of note about antler an copper.

Antler is actually the more environmentally friendly option, but it is less durable than copper, especially on glasses. Deer and moose drop their antlers every fall after the rut, and grow new points every spring. Killing the animal actually makes separating the antler from the skull more difficult. Copper sulfate mining can be outrageously nasty; mining tailings have caused great damage to the great lakes. Some years ago, some federally recognized tribes almost came to blows with a mining company that tried to transport sulfates for mining through their territory. If you care about the environment, go looking for drops in the fall, otherwise they just rot into the ground and go to waste.

Hi Jer,

Thanks for your environmentally friendly input. Enjoy your knapping!

Tom

Excellent tutorial, step by step guide, It’s nice to practically see how some of our most ancient artifacts were made.